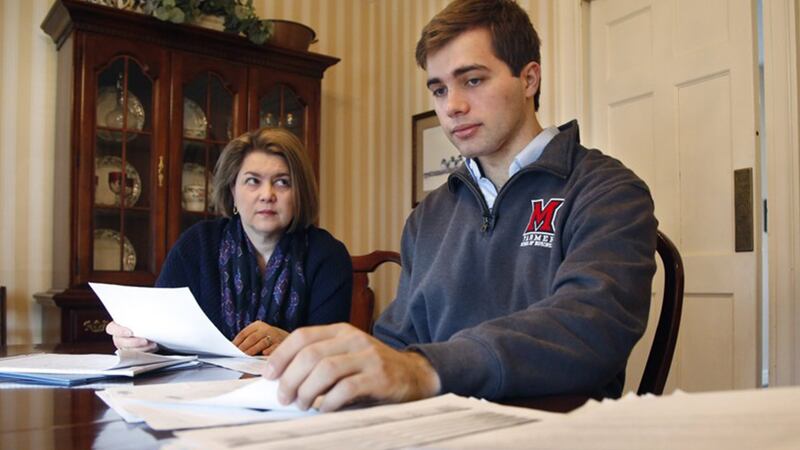

When Reid Rupp was rushed to McCullough Hyde Hospital in Oxford, Ohio last year with a broken jaw and knocked-out teeth from a bicycle accident, he needed to be transferred to a larger hospital.

The 20-year-old Miami University student's parents, Lisa and Christopher Rupp, were asked to pick whether the ambulance should take him to a hospital in Cincinnati or Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton.

They picked Miami Valley. It was in-network, near their home in Oakwood, and the family had been there before.

TRENDING NOW:

- Suspect in mass shooting at car wash pronounced dead

- Couple contracts hookworms during vacation to Dominican Republic

- Animals rescued from Puerto Rico coming to Pittsburgh for adoption

- VIDEO: 'Lunar trifecta' appearing in night sky on Wednesday

Even though the hospital was in-network — the term used to describe agreements for reduced rates negotiated between providers and insurance companies — the plastic surgeon who operated on Reid Rupp was not. Five weeks later, the Rupps received a medical bill for more than $17,000.

It’s common for hospitals to contract with doctors who are not on staff, and patients aren’t always told they will be billed separately by the doctor. If the doctor and insurance network don’t have an in-network agreement to keep costs down, patients can get stuck fighting a high bill they thought would be covered by their insurance plan.

>> Related: Empty beds, high costs contribute to Good Sam closing

Hospitals and doctors say it's difficult to pre-emptively explain what the total patient cost will be, particularly in emergencies. Out-of-network physician groups have also argued that the reimbursement rates they get from insurance companies aren't adequate for them to join a network plan, leaving them little choice but to pass their costs onto their customers.

Surprise bills more common

Surprise billing — the term used in the industry — has become more common as hospitals contract out for more services. About 65 percent of U.S. hospitals contract out their ER staffing and management, according to 2014 data from Merritt Hawkins, a physician staffing company.

A 2016 study in the New England Journal of Medicine of more than 2 million claims from one large insurer found 22 percent of its ER billings involved an out-of-network provider. And in almost every case, the patient had gone to an in-network hospital.

Congress and legislatures in different states have attempted to tackle the problem, but there is no legal protection against surprise billing in Ohio.

Lisa Rupp, a Beavercreek City Schools teacher whose insurance covers her college-age son, said the family is now fighting the $17,000 bill they received for his treatment.

Rupp said it was an emergency situation, but that Reid was stable by the time a plastic surgeon was called. She said she and her husband would have searched for a different doctor if they knew the size of the bill they were facing.

“We were not afforded that choice,” she said.

“It’s not by accident”

The plastic surgeon who operated on Reid Rupp, Dr. Kenneth Christman of Miamisburg, charged about $19,000 — $2,000 of which was picked by the family's employer-funded insurance plan. The family hasn't paid any of the balance, appealing to anyone they thought might be able to help: their insurance company, benefits broker, Christman's office, Miami Valley Hospital, their state representative and the Ohio Attorney General's office.

Christman's debt collection agency, Doctors Credit Service, said in an Oct. 17, 2017, letter to the Rupps' attorney that the doctor would like to discuss his out-of-network fees with the patients and their families "but all the hospitals that he has worked out of have blocked/prohibited him from doing this."

Cox Media Group