PITTSBURGH, Pa. — The mouthwatering aroma of fresh-baked cookies stopped wafting over Shadyside, Larimer and East Liberty after Bake-Line Group declared bankruptcy on Jan. 10, 2004. The company closed all seven of their plants, including the former Nabisco bakery in East Liberty.

The National Biscuit Company was formed in 1898 when two dueling bakery companies merged. Though it was known colloquially as “NaBisCo,” the Nabisco corporate name would not become official until 1971.

The new company’s advertising blitz and newly branded Uneeda Biscuit caused demand for its products to soar. Nabisco quickly expanded and wanted the new factories to be stylish and inspire loyalty from the workers. To that end, Chicago architect Albert G. Zimmermann was hired to incorporate the latest in safety, fire-proofing, efficiency and employee amenities.

Built on the corner of Penn Ave and East Liberty Blvd in 1918, the seven-story Pittsburgh plant was notable for its fireproof stairways, which used the tall corner towers for ventilation. The bakery also featured lots of natural lighting from large windows, and showers and locker rooms for employees.

Zimmermann’s choice of materials and construction was very typical of the company’s “Chicago Style” buildings and nearly identical buildings can be found in other cities, including Detroit, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston and New York’s Chelsea Market.

The brick façade covers a steel frame with fireproof tile surrounding the structural steel. Cream-colored enameled bricks adorn the windows and highlight elaborate keystone doorways emblazoned with “NBC” terra cotta plaques.

The bakery was expanded in 1928, when a four bay, four story addition was stretched out along Penn Ave on the eastern side of the plant to accommodate the purchase of a bread bakery. The subsidiary was named the National Bread Company, which would fully merge with Nabisco by 1940.

A much larger addition joined the bakery complex in 1948, adding 19 bays as it extended even further down Penn Ave. Nabisco factories nationwide were expanded during this time to make room for innovative new “band ovens,” which moved dough on vast conveyor belts where it was spread, cut and baked in a continuous motion. This addition would be mostly demolished during the redevelopment of Bakery Square.

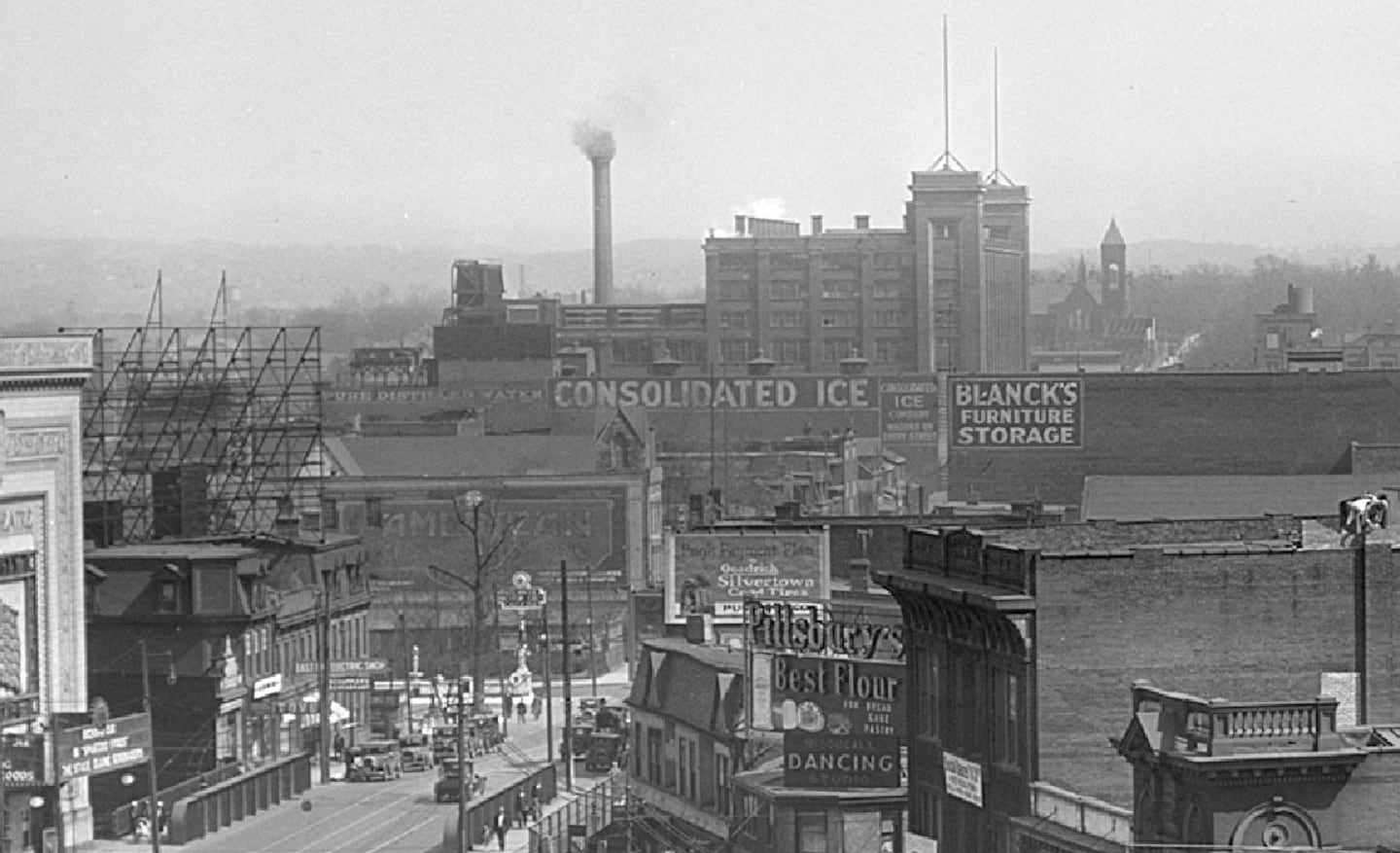

During its heyday, the tall flag-topped towers of the bakery were a beacon to the thriving neighborhoods around it. Everyone seemed to know someone who worked at the bakery and the diverse population pushed the booming East Liberty retail district to become the state’s third busiest, behind only downtown Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

After World War II, the company began to prefer long and low bakeries just as more employees started driving to work. The combination prompted most of Nabisco’s city-based factories to close in favor less expensive suburban land closer to highways. The distribution system was also transitioning from rail to trucks, which was particularly difficult for the Pittsburgh bakery. At its peak, the bakery employed over 1,000 workers in Pittsburgh.

Failed urban renewal projects in East Liberty and the collapse of the steel industry conspired to diminish the prestige and population of the area. Crime rose and the bakery was suddenly in an undesirable place.

The first attempt to close the plant was floated in 1982, but the plant survived after city and union officials rallied to convince Nabisco otherwise. It was among the oldest functioning bakeries in the company at that time.

TRENDING NOW:

Mayor Tom Murphy attempted to hold off closure again in 1998, but returned from meetings in New York with Nabisco corporate officials which he could only describe as “insulting.” Nabisco refused all public support (in the forms of tax credits, grants and financing) and shrugged off a boycott by local consumers.

The plant was operating at below 60% capacity making Ritz crackers, Wheat Thins, Better Cheddars, Swiss Cheese crackers, Ritz Bits and Twigs snacks.

With little notice, Nabisco closed the plant and left 350 employees out of work. The company cited an inability to streamline production in the historic building along with a lack of rail and highway access as reasons for the closure. Newer and more efficient plants absorbed the lost capacity and Nabisco used the savings to increase their marketing and advertising.

RIDC bought the six and a half acre site in 1999 for $10 million. It was purchased by the Atlantic Baking Company in 2001, but the revival was short-lived when the company – taken over by Bake-Line Group – declared bankruptcy in January 2004 and closed all seven of its plants. By the end of 2006 the site was vacant and declared “blighted” by the city after a failed attempt to turn the bakery into loft apartments.

Shadyside-based Walnut Capital and Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority purchased the property for $5.4 million from RIDC and announced plans in 2007 for transforming the old main factory building into offices and retail space with a new parking garage and hotel constructed nearby. Total costs for the redevelopment were estimated to be between $105 and $125 million. It took three years to renovate the structure and it reopened in 2010, along with a 110-room SpringHill Suites by Marriot also opened in 2010.

Google became the first high profile tenant, creating an initial campus of 115,000 square feet on the double height penthouse space. It was joined by UPMC, University of Pittsburgh, Human Engineering Research Laboratories, and Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute – among others – that quickly cemented the reputation of Bakery Square as a technology hub in the city.

Bakery Square businesses now employ over 3,000 people, far in excess of the original bakery.

With the rejuvenated building anchoring Bakery Square, new buildings were added all around it. Bakery Square 2.0 was constructed across Penn Ave from the old factory on the former site of Reizenstein Elementary School and Google expanded into that space, connected by an elevated two-level footbridge. Two large residential buildings (Bakery Living Orange and Bakery Living Blue) were also constructed and construction continues beyond them on dozens of townhomes called Bakery Village.

Bakery Office 3 is scheduled to be complete in late 2020 and will become home to Philips Sleep and Respiratory Care’s headquarters. Employees there will look out on Walnut Capital’s other big project this year, a refresh of the public plaza planned to open in early 2021. A large two-story glass enclosure called the Galley will house new eateries, event space and seating. A second parking garage is also being added across Dahlem Place.

Walnut Capital’s footprint around Bakery Square has been growing through additional acquisitions as well. The company recently purchased the neighboring former Matthews International offices, the Village of Eastside nine-acre shopping plaza and the former Club One Fitness property.

As the building boom of expensive housing, retail and well-paid high-tech jobs has seeped into more and more adjoining streets and neighborhoods, it has not been without controversy. Many long-time residents have complained of gentrification, especially after public housing high-rises were demolished in nearby Penn Circle and they contend that affordable apartments have become increasingly rare in the area following the rebirth of Bakery Square.

Cox Media Group