PITTSBURGH (AP) — For the two weeks that the Hackneys’ baby girl lay in a Pittsburgh hospital bed weak from dehydration, her parents rarely left her side, sometimes sleeping on the fold-out sofa in the room.

They stayed with their daughter around the clock when she was moved to a rehab center to regain her strength. Finally, the 8-month-old stopped batting away her bottles and started putting on weight again.

“She was doing well and we started to ask when can she go home,” Lauren Hackney said. “And then from that moment on, at the time, they completely stonewalled us.”

The couple was stunned when child welfare officials showed up, told them they were negligent and took away their daughter.

“They had custody papers and they took her right there and then,” Lauren Hackney recalled. “And we started crying.”

More than a year later, their daughter, now 2, remains in foster care and the Hackneys, who have developmental disabilities, struggle to understand how taking their daughter to the hospital when she refused to eat could be seen as so neglectful that she’d need to be taken from her home.

They wonder if an artificial intelligence tool that the Allegheny County Department of Human Services uses to predict which children could be at risk of harm singled them out because of their disabilities.

The U.S. Justice Department is asking the same question. The agency is investigating the county’s child welfare system to determine whether its use of the influential algorithm discriminates against people with disabilities or other protected groups, The Associated Press has learned. Later this month, federal civil rights attorneys will interview the Hackneys and Andrew Hackney’s mother, Cynde Hackney-Fierro, the grandmother said.

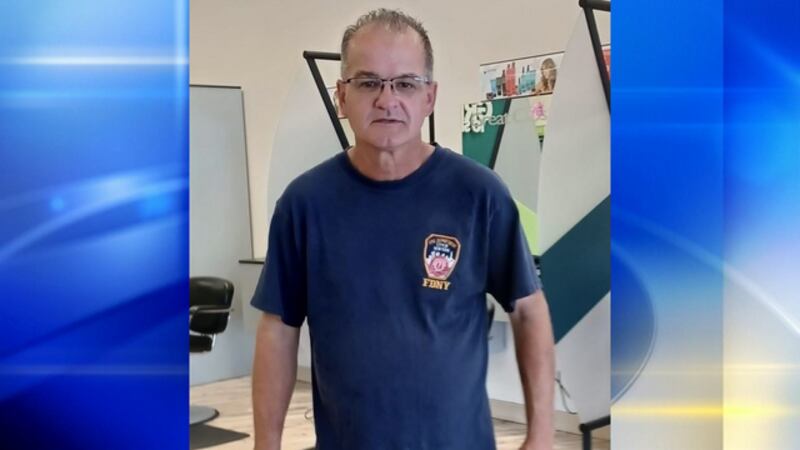

Lauren Hackney has attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder that affects her memory, and her husband, Andrew, has a comprehension disorder and nerve damage from a stroke suffered in his 20s. Their baby girl was 7 months old when she began refusing her bottles. Facing a nationwide shortage of formula, they traveled from Pennsylvania to West Virginia looking for some and were forced to change brands. The baby didn’t seem to like it.

Her pediatrician first reassured them that babies can be fickle with feeding and offered ideas to help her get back her appetite, they said.

When she grew lethargic days later, they said, the same doctor told them to take her to the emergency room. The Hackneys believe medical staff alerted child protective services after they showed up with a dehydrated and malnourished baby.

That’s when they believe their information was fed into the Allegheny Family Screening Tool, which county officials say is standard procedure for neglect allegations. Soon, a social worker appeared to question them, and their daughter was sent to foster care.

Over the past six years, Allegheny County has served as a real-world laboratory for testing AI-driven child welfare tools that crunch reams of data about local families to try to predict which children are likely to face danger in their homes. Today, child welfare agencies in at least 26 states and Washington, D.C., have considered using algorithmic tools, and jurisdictions in at least 11 have deployed them, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

The Hackneys’ story — based on interviews, internal emails and legal documents — illustrates the opacity surrounding these algorithms. Even as they fight to regain custody of their daughter, they can’t question the “risk score” Allegheny County’s tool may have assigned to her case because officials won’t disclose it to them. And neither the county nor the people who built the tool have explained which variables may have been used to measure the Hackneys’ abilities as parents.

“It’s like you have an issue with someone who has a disability,” Andrew Hackney said. “In that case ... you probably end up going after everyone who has kids and has a disability.”

As part of a yearlong investigation, the AP obtained the data points underpinning several algorithms deployed by child welfare agencies, including some marked “CONFIDENTIAL,” offering rare insight into the mechanics driving these emerging technologies. Among the factors they have used to calculate a family’s risk, whether outright or by proxy: race, poverty rates, disability status and family size. They include whether a mother smoked before she was pregnant and whether a family had previous child abuse or neglect complaints.

What they measure matters. A recent analysis by ACLU researchers found that when Allegheny’s algorithm flagged people who accessed county services for mental health and other behavioral health programs, that could add up to three points to a child’s risk score, a significant increase on a scale of 20.

Allegheny County spokesman Mark Bertolet declined to address the Hackney case and did not answer detailed questions about the status of the federal probe or critiques of the data powering the tool, including by the ACLU.

“As a matter of policy, we do not comment on lawsuits or legal matters,” Bertolet said in an email.

Justice Department spokeswoman Aryele Bradford declined to comment.

The tool’s developers, Rhema Vaithianathan, a professor of health economics at New Zealand’s Auckland University of Technology, and Emily Putnam-Hornstein, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School of Social Work, said that their work is transparent and that they make their models public.

“In each jurisdiction in which a model has been fully implemented we have released a description of fields that were used to build the tool,” they said by email.

The developers have started new projects with child welfare agencies in Northampton County, Pennsylvania, and Arapahoe County, Colorado. The states of California and Pennsylvania, as well as New Zealand and Chile, also asked them to do preliminary work.

Vaithianathan recently advised researchers in Denmark and officials in the United Arab Emirates on technology in child services.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funded a national study, co-authored by Vaithianathan and Putnam-Hornstein, that concluded that their overall approach in Allegheny could be a model for other places.

HHS’ Administration for Children and Families spokeswoman Debra Johnson declined to say if the Justice Department’s probe would influence her agency’s future support for algorithmic approaches to child welfare.

Especially as budgets tighten, cash-strapped agencies are desperate to focus on children who truly need protection. At a 2021 panel, Putnam-Hornstein acknowledged that Allegheny’s “overall screen-in rate remained totally flat” since their tool had been implemented.

Meanwhile, family separation can have lifelong developmental consequences for children.

The Hackneys’ daughter already has been placed in two foster homes and spent more than half of her life away from her parents.

In February, she was diagnosed with a disorder that can disrupt her sense of taste, according to Andrew Hackney’s lawyer, Robin Frank, who added that the girl still struggles to eat, even in foster care.

“I really want to get my kid back,” Andrew Hackney said. “It hurts a lot. You have no idea how bad.”

TRENDING NOW:

©2023 Cox Media Group