PITTSBURGH — Henry John Heinz III was a man in his prime.

The 52-year-old U.S. senator and heir to the H.J. Heinz food empire had everything going for him April 4, 1991, the morning he climbed aboard a small, twin-propeller plane in Williamsport. The short flight to Philadelphia was for him to attend a pair of hearings and a constituent meeting during the congressional Easter break.

In his 20 years in Congress — five in the House and 15 in the Senate — Heinz had an impressive portfolio as one of a dwindling handful of moderate Republicans. He boasted accomplishments on Social Security and pension reform as well as trade and environmental issues.

He was charismatic, telegenic and popular with Democrats and Republicans alike in the Keystone State. Many believed he was headed for a presidential bid.

All of that ended in a tragic flash.

Over an elementary school in suburban Philadelphia, the blades of a helicopter inspecting the plane’s troubled landing gear ripped into its wing and fin. The midair collision sparked an explosion, sending fiery wreckage from both aircraft crashing down on Lower Merion. Along with Heinz, the two pilots flying the rented plane and two men in the helicopter, the crash also killed two first-grade girls on the school playground below. Five others on the ground were injured.

Three decades later, friends and colleagues remember the legacy of a senator they say was ahead of his time.

They cite his work promoting the Clean Water Act and the cap-and-trade system to deal with acid rain, as well as his work on international trade and with his advocacy for the elderly, among his top priorities.

‘Different era for Republicans’

Grant Oliphant heads The Heinz Endowments, the Pittsburgh-based philanthropic organization that reflects the late lawmaker’s passion for environmental activism and economic development. Long before that, Oliphant served as the senator’s press secretary.

“It was a different era for Republicans,” Oliphant said. “There was a strong conservationist bent to the Republican Party and a lot of people on that side of the aisle saw the connection to the kind of life they wanted to live and a good environment.”

Heinz managed to promote environmental regulations and win elections by large margins, despite his roots in a region where many equated smoky skies with middle-class jobs.

“He bridged that gap by being able to walk and chew gum at the same time,” Oliphant said. “He got away with it because he always kept connecting it to the future and the kind of world people wanted to live in. He appreciated early that there was a connection between good environmental policy and people’s well-being. He also envisioned that the future Pennsylvania economy was going to look different. In 1983, he got the earmark to launch the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon.”

His work on trade issues earned Heinz points with the region’s corporate leaders and the unions that peopled its plants and factories.

“Way before it was cool, he was sounding the alarm on U.S. trade policy and how it was necessary to get tough on China,” Oliphant said. “He was saying that in 1987.”

Even before that, the Pennsylvania senator’s work on pension reform and partnership with N.Y. Democratic Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, promoting the reforms that would put Social Security on a firm footing for years to come, endeared Heinz to the state’s increasing gray demographic.

Mark DeSantis, today a serial entrepreneur, was among a cadre of dedicated young staffers in Heinz’s Senate office.

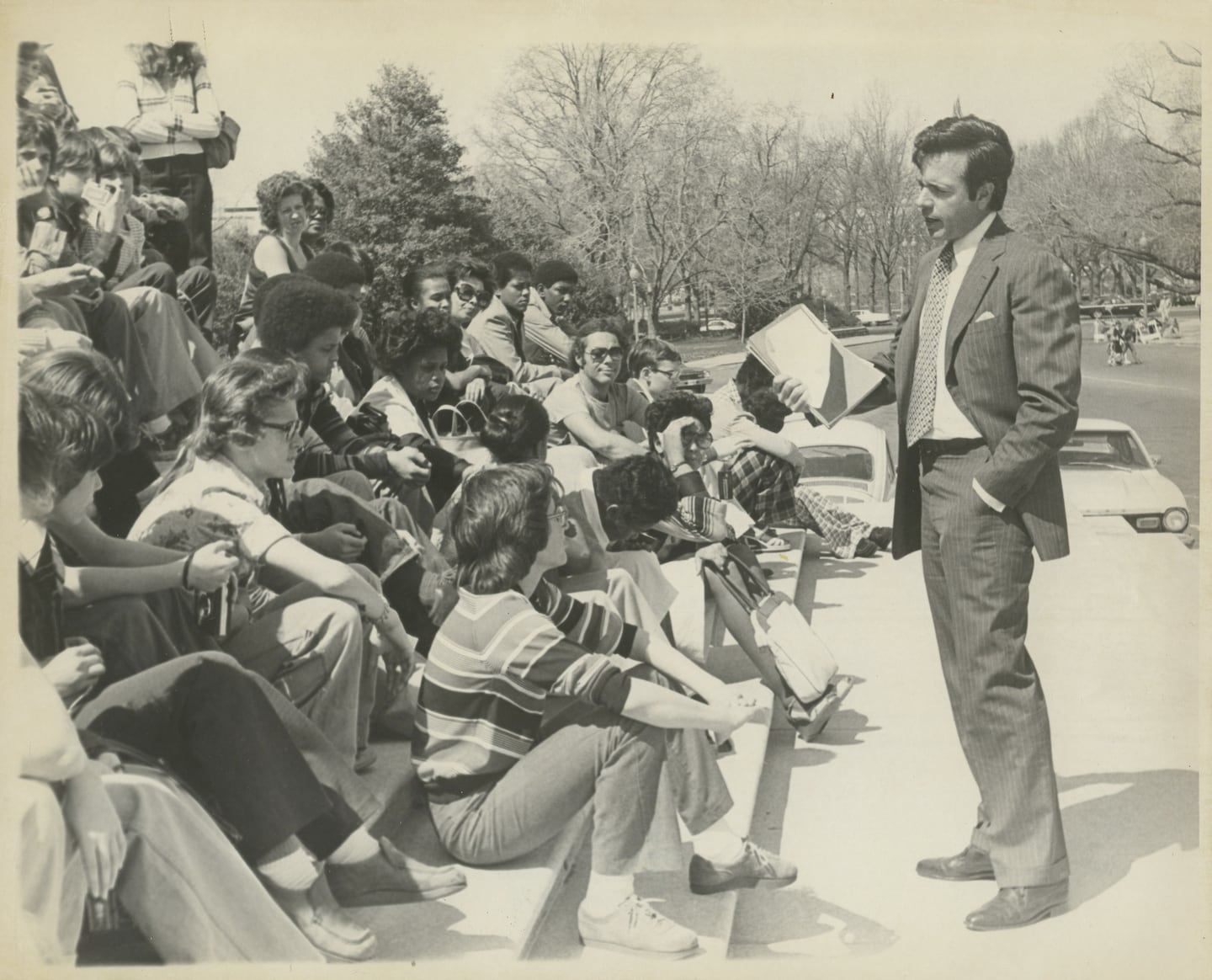

DeSantis said Heinz had a remarkable grasp of detail and worked hard to overcome any perception that he had bought his way in the world. He conducted more than 500 town hall meetings, barnstorming the state, meeting constituents in halls of labor unions, fire departments and the American Legion.

“He had a keen understanding of what was important for the state. Ask him anything about the state, about industry or agriculture, and he could recite in excruciating detail what he knew about it,” DeSantis said.

Heinz also had a reputation as a demanding taskmaster. Staffers knew that when Heinz asked for a report, they were expected to produce or find the door.

“He was demanding, but the staff was accepting of that. You just signed up for that. And he was more demanding of himself,” DeSantis said.

Former Allegheny County Executive Jim Roddey, a fellow moderate Republican, came to know Heinz well. He still marvels at his friend’s ability to cross political lines to get things done on Capitol Hill and in a state where Democrats held a significant registration edge.

In part, that may have owed to his ability to build diverse circles of friends and associates long before diversity was a touchstone in politics.

TRENDING NOW:

The late K. Leroy Irvis, a Pittsburgh Democrat who broke the color barrier as the first Black Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, was a family friend and early mentor. Legend has it, Irvis was among the influential friends who encouraged Heinz to run for public office. Those close to him say the two were close for many years.

Like many friends and supporters, Roddey insists Heinz eventually would have landed in the Oval Office.

“He was exactly the kind of person I wish we had today. I think he certainly would have run for president,” Roddey said. “If he were alive today, he would be a former president of the United States.”

On the other hand, few believe he would have had a place in today’s party.

“He would have been appalled at the personal nature of politics today, that it’s not about policy or ideas,” DeSantis said.

Native son returns

Heinz came to politics in Pennsylvania through a roundabout route.

The only child of H.J. Heinz II and Joan (Diehl) Heinz, he moved to San Francisco with his mother and stepfather, Navy Capt. Clayton Chot “Monty” McCauley, as a toddler in 1942 following his parents’ divorce. But he often spent summers and holidays with his father in Pittsburgh.

A 1960 Harvard graduate who earned an MBA at Yale three years later, he ended up back in Pittsburgh in the marketing department of the H.J. Heinz Co. in 1965 after a stint on active duty as an enlisted man in the Air Force Reserve.

He met his future wife, Teresa Simões-Ferreira, in Switzerland during a summer break in graduate school. The two married in Pittsburgh in 1966 and had three sons, John IV, Andre and Chris.

Heinz taught graduate business courses at Carnegie Mellon University for a year in 1970-71.

An obituary in the now-defunct Pittsburgh Press said that during those years, Heinz helped to build two institutions that would become Pittsburgh brand names almost on a par with the condiment kingdom.

He was among a group of investors who helped bring a National Hockey League expansion franchise — the Pittsburgh Penguins — to the city in 1966. Later, he helped Fred Rogers establish Family Communications Inc., the production company for “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

But Heinz had developed a taste for Pennsylvania politics in 1964, when he managed Sen. Hugh Scott’s reelection campaign. When U.S. Rep. Robert Corbett died unexpectedly in April 1971, that hunger resurfaced.

Political path

Heinz jumped into the fray and beat Democrat John Connolly, a well-known Pittsburgh businessman and owner of the Gateway Clipper fleet, in a special election in November 1971. He would go on to win reelection in 1972 and 1974 before making a successful bid for the Senate in 1976, when Scott retired. He was easily reelected in 1982 and 1988.

George Whitmer worked with Heinz on that first campaign. He then helped staff his first district office as a recent college graduate.

He recalled early mornings with Heinz shaking hands outside mill gates at Pittsburgh industrial giants of the day — the J&L plant in Pittsburgh, the massive Westinghouse plant in Turtle Creek and the Dravo shipyard on Neville Island.

Heinz worked to build strong ties to the unions, said Whitmer, who recently retired from PNC. He knew they would be integral to his election.

>>>RELATED: Midair collision claims life of Sen. John Heinz, six others April 4, 1991

Pittsburgh lawyer David Ehrenwerth became friends with Heinz as a volunteer during that time. He said early on Heinz assembled an informal group of local lawyers, doctors, businessmen and civic leaders he dubbed his “57 Club.” He met with them regularly and tasked them with writing papers for him.

“We developed a nice relationship. I took him around, even did some surrogate speaking,” Ehrenwerth said.

Keeping up with Heinz, who was his senior by about nearly a decade, was a feat.

“When I’d meet him at 7 a.m., we’d go to union halls in the morning, the Duquesne Club for lunch. And while we were there, he’d say, ‘Don’t eat much. We have three or four dinners to do tonight,’ " Ehrenwerth recalled.

Then there were the picnics at Rosemont Farm, the family estate in Fox Chapel. Ehrenwerth said Heinz would invite a diverse crowd, ranging from the region’s most influential civic and corporate leaders to union members who came fresh from the mills.

“I remember once, when it began to pour down rain and there were so many people there, there was no way he could get them all into the house. I asked him what we should do, and he said, ‘Let’s just stay out here.’ And there he was soaking wet, going around talking to everyone,” Ehrenwerth said, laughing as he recalled the unlikely spectacle.

He also had a peek at the private man at small gatherings at the farm.

There were the occasionally “lively discussions” between husband and wife, both of whom held strong opinions. But he said Heinz never had a harsh word for his three sons.

“He’d be tossing the kids in the pool and making the hot dogs on the grill himself. He wasn’t an absentee father. He was involved in their lives, always talking about them,” Ehrenwerth said. “His youngest son was just applying to college (in April 1991). John had gone to Yale, and I think Chris got into Yale the day he died.”

In 1995, Teresa Heinz married Boston Democrat John Kerry and was active in his 2004 presidential campaign. Neither she nor any of the Heinz sons live in Pittsburgh. But Oliphant said the family remains committed to The Heinz Endowments, its philanthropic work in Pennsylvania and the legacy of a man in his prime, gone too soon.

Cox Media Group